My father lived over 25 years in retirement, after a full academic career and mandatory retirement at age 65. (He didn’t expect to live that long; he’d grown up on the same farm with brothers who were both dead by their early 70’s, about the same age that their father had died). While in retirement, he enjoyed a comfortable life on his modest but very adequate pension from that well known teacher retirement organization.

We know from our retirement research studies that my father was near the front edge of what now appears to have been a transitional couple of generations of Americans that had defined-benefits pensions paying out benefits as long as beneficiaries lived, while food, health and lifestyle factors were significantly extending life spans.

It seems like “transitional” is an appropriate word. Today, there still are retirees or near-retirees who can look forward to a similar comfortable, extended after-work-years period. However, Artemis Strategy Group research and other studies find that this pattern won’t be sustained without big changes. Current work and saving trends are going in a different direction.

- At the upper end of the age spectrum it’s hard to envision how such large numbers could enjoy retirement as the current generation does. Not only are many current retirees benefiting from defined-benefit pensions such as those my parents had, but our government tilts its benefit payments strongly toward older Americans; a recent report noted that over 50% of federal benefits go to the 13% of the population over the age of 65.

- Aside from the government’s financial crisis specifically about the growth of long-term costs associated with those benefits to seniors, the private sector continues its march away from the defined-benefit paradigm. One result is that the proportion of Americans over 45 who are approaching the “retirement” years with pensions is declining, and a majority in this generation already recognize they are woefully behind in their personal financial preparations for anything like a comfortable retirement.

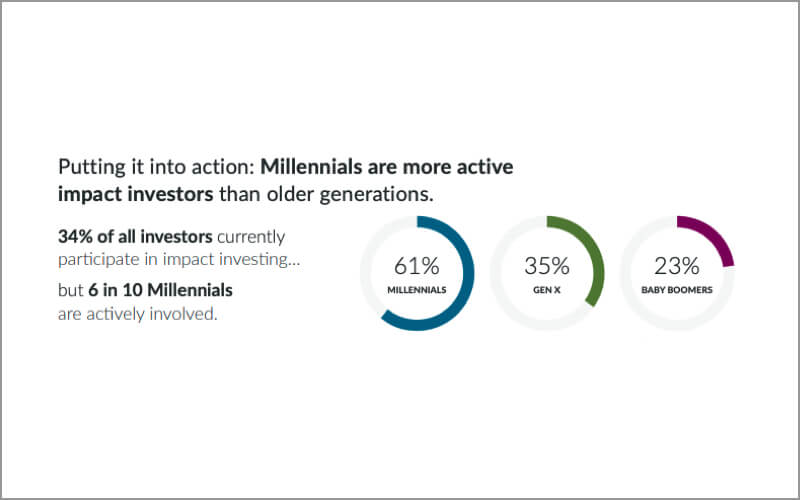

Interestingly, as the arbitrarily designated age 65 seems more and more anomalous as a formal end-of-work life, the time it takes for young people to get fully cranked-up and participating in the work force seems to be extending. And that has an impact on their financial wherewithal. In a recent study among 20-somethings, we found that less than one-third (even among the 29-year-olds!) asserted that they had achieved full financial independence, defined as breaking their ties of financial dependence on parents. At the same time, even though they were struggling to achieve financial independence, over two-thirds had already begun the process of saving for their own retirements.

Quite an intriguing transition in generational retirement planning: generations at opposite ends of the spectrum seek financial independence, but because of economic, political and personal circumstances, use very different approaches to get there.