This is a continuation of notes from the Federal Reserve’s 2015 Economic Mobility conference, a gathering that brings together thinkers from around the country who are focused on understanding the forces impacting the economic health of Americans. This conference was built strongly around an assessment of how the American Dream concept has been challenged, and what that means for the future of our culture.

The term “American Dream” became part of public conversation when James Truslow Adams used it in his 1931 book The Epic of America—though Walter Lippmann was arguably the first to use the phrase years earlier. It was the promise that a higher material standard of living would come to the next generation through the hard work and abilities of previous generations. It came to be an article of faith among Americans.

The news, as reported in this conference, is not good. But as is often the case, it’s important to make sure we’ve seen the whole picture. We were intrigued that in spite of some serious gloom, a sliver of a silver lining can be seen.

First, the bad news. This year a Gallup survey finds that 74% of Americans doubt the ability of their kids to do better than themselves, the highest negative view on this measure since 1992.

There’s been a litany of bad news about how we’re doing as a culture on achieving the American Dream over the last decades. Talking about his book Inequality, Nobel economist George Stiglitz highlighted the startling finding that the inflation-adjusted median income in the U.S. today is lower than it was 25 years ago. And for a white male in his prime earning years the inflation-adjusted median is lower than it was 40 years ago. Stiglitz goes further in asserting that federal government policies aimed at achieving financial stability have exacerbated economic inequality.

Pushing this point about how inequality is being perpetuated across generations, Robert D. Putnam, author of Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, concentrated his analysis on how changes in income distribution, class segregation and fraying family and social bonds have impacted the ability of young people to reach for the American Dream. One of his more startling observations concerns the fraying of the social structure that has traditionally helped less-advantaged kids reach for opportunity. His conclusion is that poor kids are more socially isolated even within their families, but especially in their churches, their schools and their community organizations. A consequence of this isolation is a dramatic decline in trust among those kids of all the institutions that ought to be helping them.

Katherine S. Newman, author of Falling from Grace: Downward Mobility in the Age of Affluence, honed in on an internal motivational force that is a critical ingredient to effective decision making: the concept of personal control. She highlighted the negative impact of parents’ job loss on their kids’ sense of personal control. Two of the observations she makes point to the difficulty of breaking a bad cycle. One is the extent to which our culture has come to associate economic success with self-worth, and even moral superiority. The other observation is one that we intuitively understand: kids are impacted by their parents, and living in situations that appear to make success less a factor of personal effort and more subject to external forces makes gaining that critical sense of personal control harder.

Now for a little good news. It’s easy with such a string of negative analyses to feel we’re completely off track as a country. Perhaps the speakers realized this, so they paused to reflect on a few notes of good cheer. While the inequity issue is significant, there are quite a few metrics of overall societal progress: lower rates of teen pregnancy, lower rates of lead exposure, lower levels of drug use, higher rates of achieving a college education, more people covered by health insurance and lower crime rates.

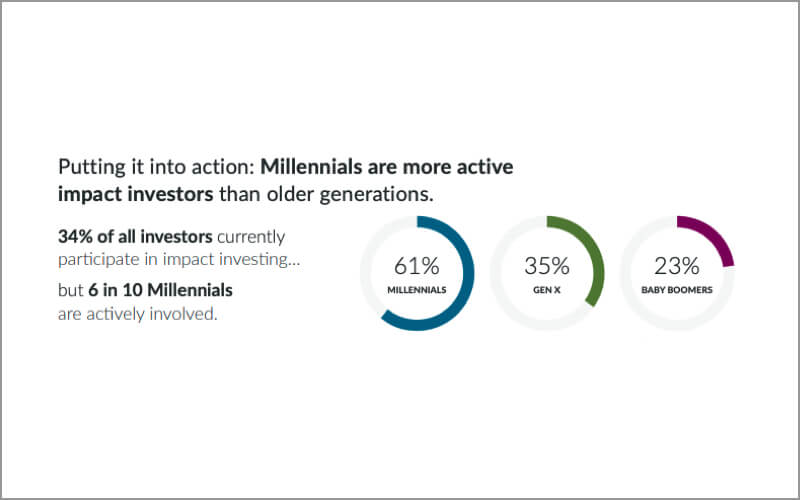

One of the most cheering of all: Millennials are optimistic about the future. Whole families are rearing the children of Millennials, and, for many, the cross-generational transfer of income is well underway.

While not mentioned by this group of speakers, we’re struck at how personal technology has given those at the lower end of the economic spectrum new access to tools that can increase their actual and perceived control.

This potential opportunity is borne out in our own financial trends research. We’ve found that Americans are working toward financial stability from a place of self-reliance. Values have shifted to a more defensive outlook, with a growing emphasis on gaining a sense of personal control of finances and being able to enjoy life and less emphasis on achievement.

Perhaps the traditional concept of the American Dream, and its focus on a specific picture of upward mobility and prosperity, has become outdated. After all, as a nation of immigrants, much of our early collective dream had to do with starting anew and building something from next-to-nothing. Perhaps, as the explosive growth of the nation’s economy has slowed since the coining of the term and as we become more of a multi-generational country, the American Dream must evolve. What this Fed conference and its speakers make us realize is that there are structural problems we need to work on to truly make it a possibility for all.

In our work, we’ve been encouraged at both the policy and the micro economic level. From a policy standpoint we see the opportunity to turn the U.S. into more of a nation of savers. At the individual level, we see the assistance that new technologies can provide to individual citizens that helps them overcome at least some of the barriers that face them today.