Americans’ priorities and behaviors already are changing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of these changes will continue and be long-lasting. The challenge for any forward-looking enterprise hoping to adapt properly is to begin developing a sense of what is most likely to happen.

While the pandemic and the response to it are unique in several ways, there are lessons to be learned from prior shocks to the system. Over the last decade, Artemis Strategy Group has studied how consumer behaviors and values have evolved and been influenced by the Great Recession of 2008/2009.

This commentary offers a few of those lessons from our analysis of the Great Recession, and an assessment of how these factors are likely to apply as the U.S. works through, and ultimately recovers from, the COVID-19 pandemic experience. We include a brief comparison of the Recession to today’s circumstance to help gauge the applicability of these lessons.

Lessons from the Great Recession

- Recovery took a long time. For seven years after the end of the Recession, the memory and impact of it was a dominant presence guiding how a majority of Americans thought about their lives and financial affairs. For those who had assets, it took an average of five years (or until 2014) to make it back to where they’d been in 2007. Most felt the loss of time even as they began to recognize their recovery. More broadly, many took longer to recover: We found in our 2016 MAP (Motivations Assessment Program) survey [PDF] that one-fifth of Americans described their top current financial priority as recovering from a past setback, often directly referring to the Recession.

- The response moved through several stages. The Stages of Grief framework propounded by Elizabeth Kubler Ross and David Kessler provides an appropriate analogy to the tone and stages of response following the acute crisis period. The initial shock and denial soon gave way to manifestations of anger — at the individual and societal levels, as evidenced by movements such as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street — that were widespread for several years and have contributed to a generally angrier culture even today. The bargaining phase tended to concentrate around those most seriously set back, but at the individual level our surveys measured significant widespread levels of anxiety and depression for at least five years following the acute crisis. It took until the late teens to see broad concurrence around the final stage of grief, acceptance, when other forces overtook Recession memories.

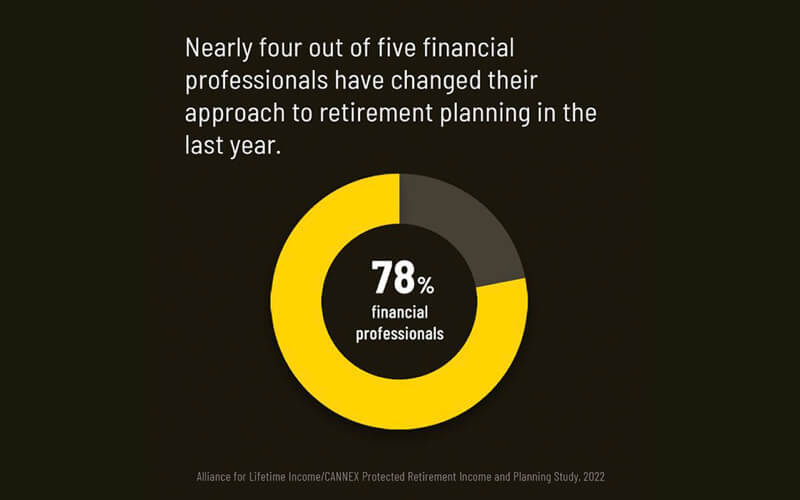

- The Recession accelerated changes in how Americans approach financial affairs. Since the crux of the crisis was a loss of financial control, it makes sense that many of the changes in behavior coming out of the Recession related to ways to regain that control. The Recession accelerated movement of consumer financial interactions online, facilitated by the introduction of new tools designed to provide greater financial control, insight and flexibility. Lost trust in some of the largest financial institutions contributed to the explosion of the FinTech industry, offering alternative channels to personal financial management.

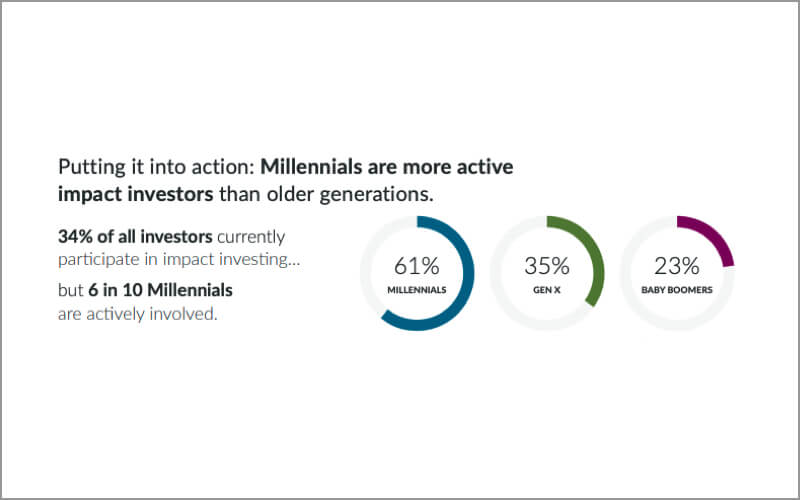

- Many people found their priorities to achieve personal values changed. We emphasize these changes because personal values are the underlying motivators that drive most decisions, and the motivational pathways people follow to achieve those values tend to be stable over time. Changes only occur gradually or in response to tectonic events. That’s what happened in 2009. Trust has always been a key element underlying individual decision motivations; it became a more prominent driver of decisions in the teens, and harder for providers to attain. In the financial realm specifically we measured a shift by 2016 in the relative weight of different personal values and the associated rational/emotional thought pathways driving financial decisions. We referred to this phenomenon as the “search for stability.” Other influential changes that we noted during the middle stages of adaptation to Recession effects went well beyond the financial realm. In surveys of affluent Americans conducted for several years after the Recession, two-thirds asserted that they had developed a greater appreciation for non-material wealth in their lives. Nearly as many said that the Recession caused them to reassess their life priorities.

Comparing the two shocks to the American economy

The applicability of these lessons depends on the comparability of circumstances. The COVID-19 crisis shares a number of characteristics with the Recession:

- Both were caused by forces outside most people’s frame of reference (derivatives; bats)

- Both impacted some portions of the population acutely, but almost everyone experienced significant negative effects

- Both have required new solutions, including massive government intervention but also a burst of innovative workarounds and new alternatives

- Both imposed long-term costs, on societies and individuals

The current COVID-19 crisis has some unique characteristics:

- Its impact is significantly broader, encompassing health, finance and significant aspects of work, education and leisure activities

- It has required significantly greater and more universal behavioral changes

- Beyond the immediate medical and financial responses, the primary societal solution — social isolation — is a dramatic test.

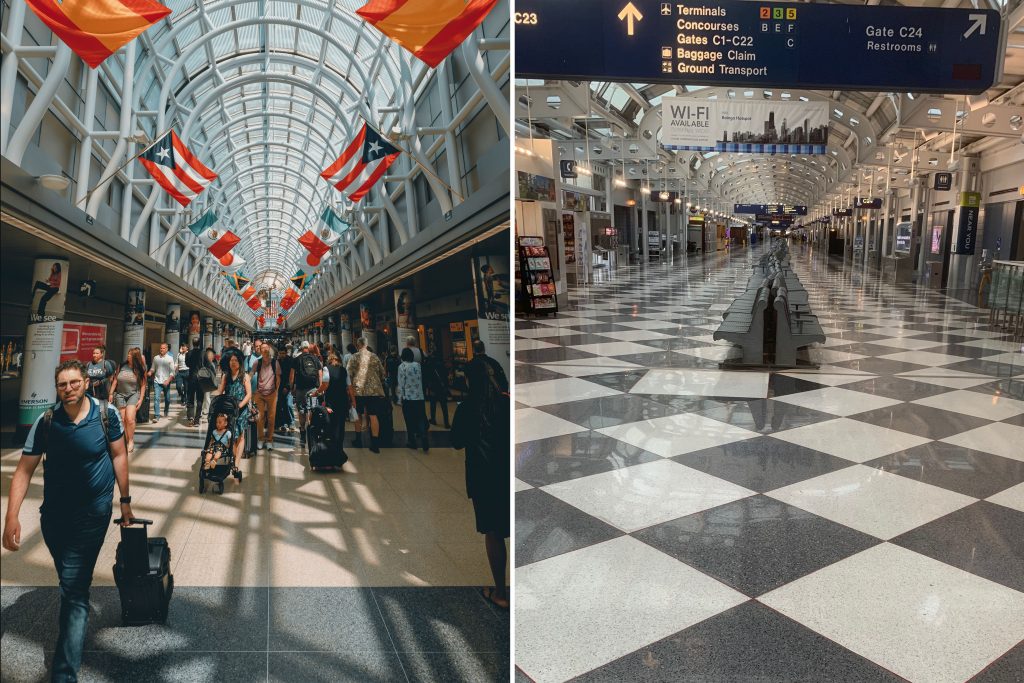

One medical allusion is that just as doctors do with a very sick patient to buy time, we’ve placed society into a coma, intentionally stopping a vast array of the normal activities people are used to. An interesting interpretation of the impact of this coma is that it has served as a giant simulation pushing Americans to envision what a very different way of living might feel like.

What should we expect?

First, the impact of this COVID-19 crisis will be lasting. We will go through several stages. We’re already moving into the third stage: the first was the long-coming “Houston we have a problem” recognition; the second was and is the massive mitigation and financial acclimation stage. Recovery might be too positive a characterization of this third stage; perhaps “adjustment” is a better way to describe what promises to be the next phase of re-starting the economy.

People coming out of medically induced comas often think, feel and act differently than before. The chief questions about the current situation’s social isolation–induced behaviors and the factors that will help achieve motivating values are as follows: Which will snap back to where they were “before,” which will evolve gradually and which may represent fundamental changes that need to be recognized by those offering products and services to society.

On the behavioral side, we’re confident that Americans will be happy to get back to eating out and attending entertainment and sports events as soon as it’s feasible, though perhaps with more restraint. It’s quite possible that cooking, sewing and many of the other lost arts that were rediscovered during social isolation will see new growth. The technology-aided remote services that have substituted for many in-person activities will fall back some, though we’re projecting their growth trajectories will continue to accelerate. The key changes that appear most likely to accelerate are the online applications in health care, food service and other critical services.

The relative weight of desired emotional outcomes that drive decisions won’t change universally, but there are some important elements that we’ll be watching closely. Our top candidates for value shifts include the following:

- Personal health consciousness and care

- Greater acceptance of remote health delivery and more extensive record sharing

- Reconsideration of work-life balance and, among older Americans, retirement timing

- Importance of social engagement, including philanthropy and volunteering

- Shifting trust in institutions, with winners and losers

- Possible changes in financial confidence and planning

A first-round strategy for discovering and responding to changes

As previously stated, people coming out of a coma often see the world, and their place in it, differently. It’s worth examining how our worldwide induced coma will affect what’s newly important to people and how best to help them achieve that.

Our fundamental takeaway is that we’re in a behavior- and priorities-altering environment. The context of our lives has shifted so dramatically that the rational and emotional elements that underscore how we make decisions will change. These changes may lead to a different mix of motivational connections driving many decisions. How will our yearning for connection and a sense of belonging be achieved in the post-coma world? How will a sense of security be established amid a changed environment of financial and health uncertainties? A sense of independence is a strong value for many in specific contexts — will that rise in importance, or will it be replaced by a recognition that dependence on some government and community services are more vital?

In this kind of environment our strong inclination is to frame a strategic inquiry broadly, with a motivational analysis that encompasses a landscape of consumer decisions extending beyond the bounds that an organization might usually examine. A standard approach for innovation efforts, this is even more important when we’re convinced that fundamental changes in the motivational structure of decision making might be shifting. This doesn’t mean wallowing in the sea of interesting COVID-19-period behavioral trends; rather, preparation for this motivational analysis benefits from a disciplined hypothesis-building process — “what ifs” — and likely some preliminary testing of those hypotheses. Timing is also an issue; the dynamic aspect of this crisis — we’re still in the middle of it — dictates re-checks along the way.

This is certainly an unpredictable, challenging business and policy environment. And it is still in its formative stages.